Over the past two years, climate change has had devastating effects on coral reefs around the world. In the Caribbean, particularly the Windward Islands, sea temperatures were the hottest ever recorded at over 31C. The level of heat stress measured in Degree Heating Weeks reached 25, which according to NOAA translates as a “Risk of near complete mortality” from coral bleaching.

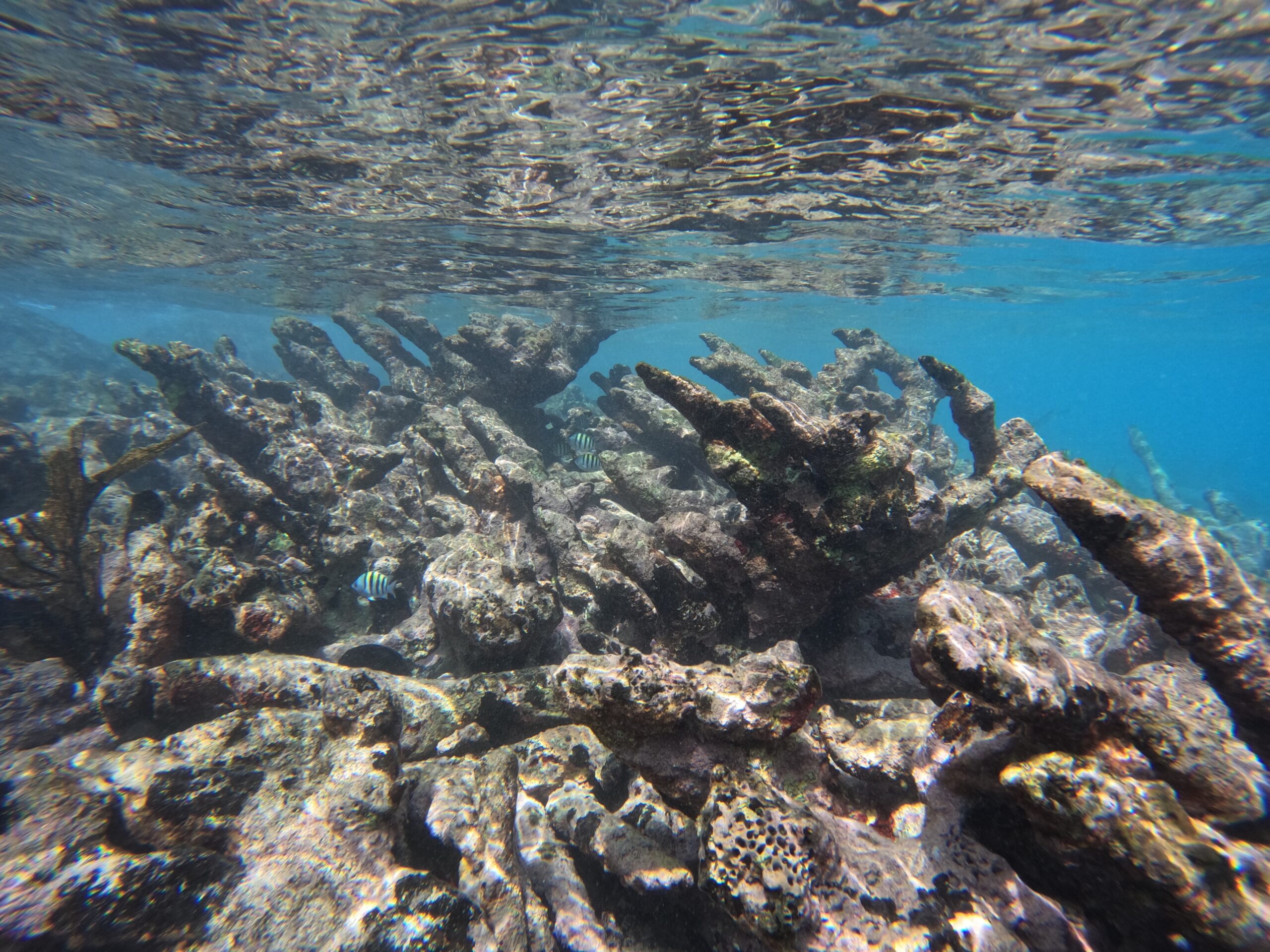

Our restoration teams in St Lucia and St Vincent and Grenadines have been doing extensive surveys looking for elkhorn and staghorn survivors – and it’s not looking good. The sea has been too rough to survey the windward coasts, so we hope we will find some there when it is calmer. In our nursery in Saint Lucia, we have some surviving elkhorn and staghorn genotypes because we moved them into deeper water, but almost all our outplants and source colonies have died. To make matters worse, last year’s coral bleaching comes on the heels of the terrible SCTLD coral disease, Category 5 Hurricane Beryl, and the severe bleaching of 2023.

Marine scientists across the region are monitoring the situation with shock and almost despair. Some are asking whether coral reefs have passed a tipping point where recovery will not be possible. A regional group of marine biologists supported by the Caribbean Biodiversity Fund have recently set up the Caribbean Coral Health Forum to discuss what the next steps should be to conserve and restore coral reefs. It is clear that we need to re-evaluate our restoration strategy and consider all options.

The main aim of coral restoration is to assist corals to adapt to a warmer world. To do this, we need to speed up natural selection by helping the more resilient corals grow and reproduce with a high level of genetic diversity. The more genetically diverse a population is, the more resilient it is. A simple rule is to have fragments from at least 35 individual corals taken from different locations to ensure that over 95% of the genetic diversity (allelic diversity) of the population is captured. The problem facing coral restoration programmes in the Eastern Caribbean is that it is becoming increasingly difficult to find that many surviving colonies within one country.

More importantly we now need to do what many scientists are recommending and start moving corals from hot areas to cooler areas – it is called assisted migration. The Meso-American Reef Complex has shallow waters that are on average 1°C degree warmer than the Eastern Caribbean during the summer months. The corals there have adapted to warmer conditions and some have even survived 34C!

For the survival of Caribbean coral reefs, it is now critically important that scientists and policy-makers work together to facilitate the movement of corals across national boundaries to help establish regional coral gene bank nurseries in each country. Scientists should develop protocols to ensure disease transmission risks are minimised. The time has come to think outside the box – and we don’t have much time.

The views expressed in these articles are for information only and do not represent the official position of the Caribbean Biodiversity Fund or its partners.